Post by Fadril Adren on Oct 5, 2015 18:09:30 GMT -5

HAIL CAESAR – THE COMBAT SYSTEM

Another missive from Hail Caesar author, Rick Priestley – this time Rick gives us an insight into the combat system…

Hail Caesar

Rick: This time round I’m going to talk about the Hail Caesar combat system in a bit more detail. Quite a bit more detail. In fact I’d recommend pouring yourself a tot of something and settling down for this one as I do go on a bit. Hand-to-hand fighting is one aspect of our ancient game that is distinctly different from its Black Powder predecessor. Where Black Powder places the emphasis on musketry and manoeuvre, Hail Caesar reflects the more prolonged but ultimately decisive clash of hand-to-hand fighting in pre-gunpowder warfare. Of course, some ancient armies are big on shooting – and these guys have their place in Hail Caesar too – but in terms of an entertaining and challenging wargame it has to be hand-to-hand fighting that counts in the end.

In Hail Caesar units of troops have a basic stat-line, and different types of troops have different standard stats: heavy infantry, medium infantry, light infantry, skirmishers, archers and so on. In addition, units that are particularly fighty, stubborn, or which have higher than usual morale have their stats adjusted to their advantage. Similarly, troops that are a bit iffy may suffer a reduction in one or more stats, as you might expect. In addition, units that are deemed to be under strength or small have all their stats reduced to reflect this, and –yes you guessed – units that are large get a boost.

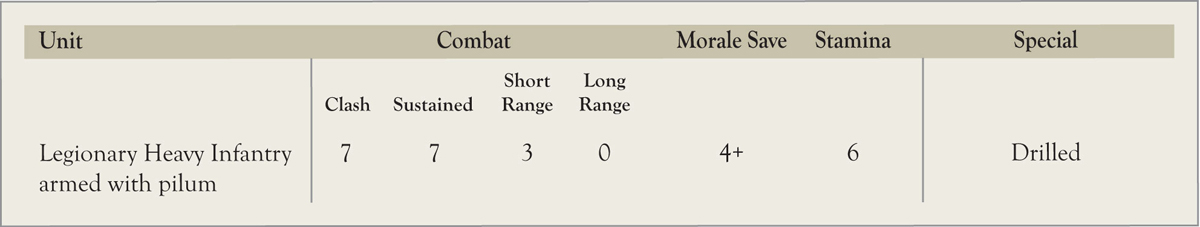

Fighting stats. Units have four different fighting stats, namely Clash Combat, Sustained Combat, Short Ranged Combat, and Long Ranged Combat. Long Ranged Combat is only used for shooting over a distance, but all the other stats are used during hand-to-hand fighting – including the Short Ranged Combat stat. These stats are generally referred to as Clash, Sustained, Short and Long.

Clash. This is the number of dice rolled in the first round of any hand-to-hand engagement regardless of whether the unit charges or not. We assume that troops who would naturally press forward into a fight would do so even where they are not ‘charging’ as defined within the game. This clash value therefore reflects the impetus from such troops. The normal value is 5 for light infantry, 6 for medium infantry, and 7 for heavy infantry. In the case of cavalry, clash values are generally a bit higher, 8 for medium cavalry and 9 for heavy and cataphracts. Light cavalry have a clash value of 7 but are often fielded as small units which generally have clash (and sustained) values 2 lower – so 5.

Sustained. This is the number of dice rolled in the second and all subsequent rounds of any hand-to-hand engagement. In the case of infantry this is usually the same as the clash value. Infantry are good at fighting sustained combat and the heavier the infantry the better they are. Cavalry drop from their clash values to 6 for heavies and cataphracts, and 5 for medium and lights (a mere 3 for small units of lights). This makes cavalry quite poor at sustained fighting except against other cavalry, and even then they are vulnerable to fresh cavalry entering the melee in subsequent turns.

Short. This value is used for short ranged shooting in the shooting part of the turn, and by supporting units in the hand-to-hand combat part of the turn. For supporting units, the short value is the number of dice rolled in combat regardless of whether it is the first round or subsequently. Supporting units are engaged in combat, but either marginally so or because they are positioned to the flanks or rear of a unit that is fighting. We’ll get to how supports work in Hail Caesar in a minute. For now it is worth bearing mind that typical values for supporting units are 3 for full sized infantry and cavalry units and 2 for small units.

Aside from its fighting stats, a unit has a Morale value and a Stamina value. Anyone who plays Black Powder will be familiar with these two chaps. The Morale value is the basic chance of avoiding a hit expressed as 6+, 5+ and 4+, i.e a dice roll of 6, 5 or more, and 4 or more. Lights troops usually have a value of 6+, medium 5+, and heavy 4+. Stamina is the number of casualties a unit can suffer before its fighting ability is compromised. In Hail Caesar stamina is generally 6 for standard sized infantry and cavalry units, 4 for small units and 8 for large ones. Once a unit has suffered its full stamina value number of casualties it is referred to as ‘shaken’. Shaken units fight with dice penalties, are vulnerable to break tests, and are unable to charge against an enemy. Note that in Hail Caesar the typical stamina value is 6 as opposed to 3 for Black Powder. This allows for a little more toing and frowing in a combat and means that troops tend to stick around a little longer.

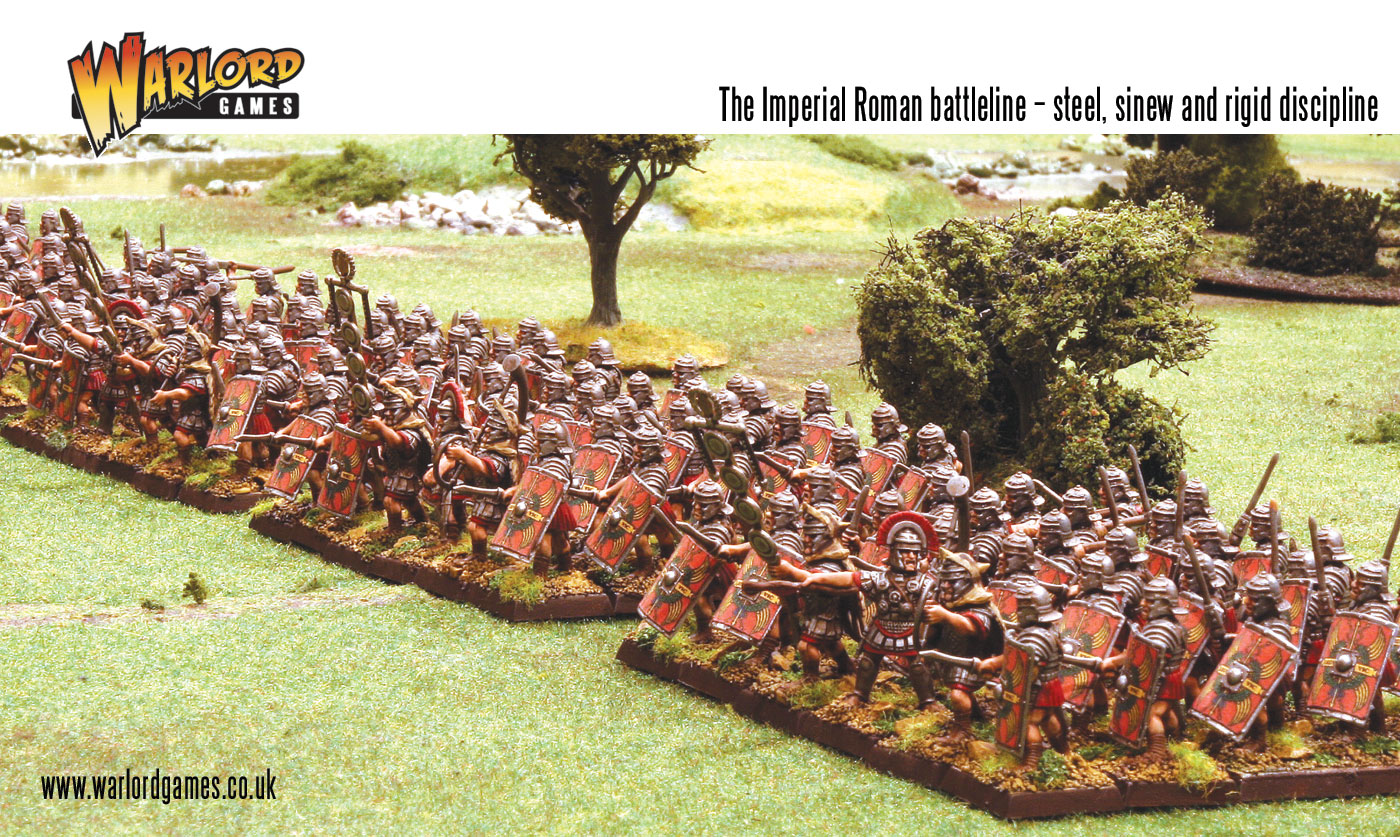

Right – with all that in mind here is a basic stat line for Roman legionaries – everyone’s favourite heavy infantry, noble champions of civilisation and all round top fellers. Step forward Marcus!

Aside from the stats already discussed we see that our Romans are heavy infantry (HI). Heavy infantry enjoy some protection from missile fire to their front (a -1 to hit modifier) and they are able to close ranks in combat. Closing ranks reduces their ability to inflict damage but increases their morale roll and therefore acts as a damper on the number of casualties both inflicted and suffered by the unit. As legionaries our lads are armed with stout swords and hefty pila: heavy javelins designed to be thrown immediately prior to contact. These have a special rule in Hail Caesar, reducing the Morale value of the enemy in the first round of all combat engagements. In addition, legionaries have the drilled special rule. This means that they can pass through other formations of drilled troops without risking disorder, and they get one free move when their commander fails to issue an order to them. Legionaries can also be elite (which gives them a chance to avoid disorder altogether), tough fighters (a re-rolled attack dice), and they can be allowed formations such as the testudo and the wedge. We won’t worry unduly about these more detailed rules for now.

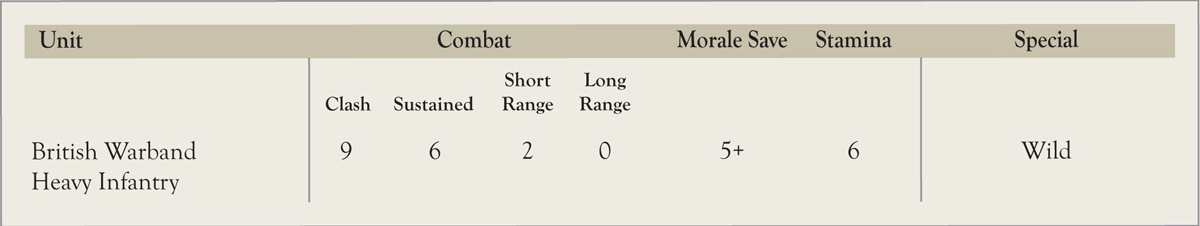

Whilst we are thinking of things Roman let’s take a look at their favoured opponents – great hairy barbarians in warbands, whether these be Britons, Gauls, Germans or Dacians. Warbands are deep massed formations – generally four deep in gaming terms although in Hail Caesar this is more a matter of looks than anything. Warbands are not the most disciplined troops but they are famously hard-hitting on the charge. This is reflected in their stat line with heavy emphasis on the clash value. So long as Roman legionaries can withstand a warband’s initial charge they will generally gain the upper hand. For warbands to win they have to mass together with supports and strike all at once. This is the stat line for a typical warband.

Warbands have a high clash value, often 9, but a reduced short value of 2, which makes them poor at supporting. Their morale is standard for medium infantry at 5+ and stamina at 6. Warbands often have the wild fighters special rule. This entitles the unit to re-roll up to three missed attacks the first time they fight in the game. This bonus only applies once during the game, so it’s important not to fritter it away against inconsequential opponents. Warbands can also have other special rules that enhance their fighting values such as tough fighters, fanatics, and eager – but we need not worry about these for now.

EXAMPLE OF COMBAT

To show us how combat works were going to fight our Roman legionaries against a Briton warband. We’ll start one on one to begin with, as that’s the easiest way to explain the basic mechanics. Play alternates in hail Caesar, so either the Romans or Celts will be moving into contact by means of a ‘charge’. Let’s start with the Britons charging home upon the Romans.

The Briton player starts by rolling his attacks. He rolls 9 dice because his clash value is 9. The basic chance of scoring a hit is 4, 5 or 6, but charging units always add +1 to the dice so rolls of 3, 4, 5 or 6 will succeed. Let’s imagine the dice turn up 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5, and 6 = 3 misses and 6 hits. As the Britons have the wild fighters special rule, and this is their first fight of the game, they are allowed to re-roll up to three misses. Let’s imagine we roll 1, 3 and 6, converting two of the misses into hits for a total of 8 hits.

The Romans must now test their Morale to determine if hits are converted into casualties. The Romans have a Morale value of 4+, so rolls of 4, 5 or 6 will ‘save’ the hits whilst rolls of 1, 2 or 3 result in casualties. 8 dice are rolled – one per hit – and average scores give 4 casualties – i.e. half the hits will be saved. 4 casualty markers are placed on the Roman unit. We use model casualties for this, but players can use chits, tokens, distinctly coloured or shaped dice, or just note the result down if you prefer.

The Roman player replies by rolling his attacks – 7 dice as the Romans have a clash value of 7. There is no reason why the Roman player can’t go first as fighting is assumed to be simultaneous, but it is usual for the side that charged to go first as this just feels right. Our Romans need rolls of 4, 5 or 6 to score hits and roll 2, 3, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 6 resulting in 4 hits (3 or 4 would be ‘average’).

The Celts must now test their Morale to determine if hits are converted to casualties. In their case this is 5+, meaning rolls of 5 or 6 will ‘save’. However, the Roman pilum special rule means that enemies suffer a -1 Morale penalty in the first round of combat. Consequently, the Britons will have to roll 6s to avoid casualties. Let’s imagine the Britons get lucky and roll 3, 4 5 and 6 and suffer 3 casualties. Once both sides have fought, the side that has caused the most casualties is the winner. You will see from our example that the match is very close, with average dice rolls on both sides tending to result in equal casualties or thereabouts. In our example the Britons have won by 1. This means the Romans must take a combat break test because they have lost the combat, applying a -1 modifier to the result because they lost the combat by 1 casualty difference.

The Roman player consults the break test chart and rolls 2D6 (two dice rolls added together for a score between 2 and 12). High scores are good – low scores are bad – and if the Roman player rolls an average 7 this gives a score of 6 with the -1 modifier. This gives a result of ‘give ground in good order together with supports’. Units giving ground move 6” directly backwards. Our Romans don’t have any supports, so the unit simply moves back 6”.

Our Britons now have the opportunity to make a follow-up move. This can be to retire, to stand where they are, or to move back into contact with the Romans. In our case let’s imagine the Celts follow up back into touch. The combat ends for the turn. In the following (Roman) turn the two antagonists fight again.

The Briton player takes up the dice once more. As in the first round, it doesn’t matter which side goes first, but as the Britons are ‘winning’ we give them the honour. As this is the second round of combat the Britons are reduced to 6 dice because their sustained value is 6. As they are winning the fight they get to add +1 to the dice score, so they will score hits on rolls of 3 or more. Let’s imagine they score an average 4 hits. With the Britons’ re-roll expended in the first round that leaves the Romans with 4 hits to save.

The Roman player rolls 4 dice – one per hit – and needs to score the unit’s Morale value of 4+. Once again we shall assume average results with 2 hits saved and 2 hits resulting in casualties. This gives the Romans a total of 6 casualties – 4 suffered in the first round and 2 in the second. As 6 is the unit’s stamina value this means the Romans are now ‘shaken’.

The Romans now get to fight back. They need rolls of 4+ to score hits but their sustained fighting value is 7. Average rolls will result in 3 or 4 hits. Let’s be generous and assume 4 hits land on the Celts.

Our Britons roll 4 dice and need 5 or 6s to make their Morale saves. Because it is the second round of combat the Roman pilum rule no longer applies. Let’s imagine we roll 2, 4, 4 and 6 saving 1 of the hits. This results in 3 casualties. The Britons have now suffered a total of 6 casualties, 3 in the first round and 3 in the second round. This means the Britons are also ‘shaken’. The Britons are also unfortunate enough to have lost the combat by 3 casualties to 2 – a difference of 1.

The Britons must take a combat break test with a -1 modifier. 2D6 are rolled and let’s imagine we score 5, which equals a 4 with the -1 modifier for the difference in casualties. A result of 4 is ‘break if shaken – otherwise give ground together with supports – all disordered’. The Britons are broken and flee away in blind terror. We just remove the whole unit all at once. In Hail Caesar broken units are removed as if destroyed, they don’t continue to flee over the battlefield, although we might imagine individual warriors doing just that.

As you can see this second round was also pretty close. Both units were shaken in the second round, which means the Romans will have to rally successfully before they can-move into combat once more. With an average break test roll of 7 the Britons would have held on with a ‘give ground’ result. If you fight this sequence for yourself you’ll see that both sides are fairly equally matched with the Romans winning about half the fights and the Britons about half. The first turn can go badly for the Romans if they are unlucky with their Morale saves or attacks. Any unit taking a break test is always vulnerable to a poor dice roll, although an infantry unit that is not already shaken does need a result of 2 or less to break. Shaken units are more vulnerable – needing only 4 or less to break – but the chances of a unit suffering 6 hits in the first round of combat are slim. Of course, where units are already worn down by earlier skirmishing or missile fire it is another matter, and often the odd casualty suffered prior to combat will make all the difference.

EXAMPLE OF MULTIPLE COMBATS

In Hail Caesar units are engaged in combat whether they are fighting or supporting. Fighting units are those whose centre-front position (the exact middle of the front of the unit) touches the enemy. This position is also referred to as the ‘leader position’ as it’s where the unit’s leader is normally placed. When a unit is fighting against an enemy the enemy automatically fights back whether its own centrefront touches or not. As units are obliged to line up as they charge it is usual for units to fight one on one to their front.

Supports are friendly units positioned directly beside a fighting unit, or directly behind a fighting unit. These guys contribute to the fight either by harassing the other side’s flanks or by lobbing missiles into the massed ranks of the enemy from beside or behind the fighting unit. A fighting unit with a friend to its left, another friend to its right, and a friend behind, has three supporting units. A unit can only be supported by one friend to each flank and by one behind (although there are exceptions to allow for multiple rear supports to create a ‘Boars Head’ type of formation, but this is special rule we need not concern ourselves with for the moment). The placement of supports works a little differently in Hail Casear than it does in Black Powder. In Black Powder supports only have to be within 6” of the unit they are supporting. In Hail Caesar supports have to be right next to the fighting unit they are supporting, or directly behind in the case of a unit supporting from the rear. In both cases supports are supposed to be touching, making a continuous battleline or deep formation. In practice, in our own games we usually allow a little leeway, generally speaking an inch of grace, just to make units easier to move on the tabletop. Technically, this convention is known as the Tamworth Inch as it neatly expresses the engineering tolerances reputable used by the (now defunct) Reliant Motor Company of Tamworth when constructing motorcar chassis; otherwise referred to as ‘near enough’ or ‘that’ll do’. Supporting units make attacks in a similar way to fighting units, although it is worth bearing in mind they never get a bonus for charging or for winning a combat. The supporting unit makes its attacks against the same enemy unit as the friendly unit they’re supporting. The number of attacks is the short stat value, which in most cases will be 3 for full sized units and 2 for small units. In the case of warbands this value is also 2 as these large, massed units of barbarians are judged to be not especially well coordinated and therefore less effective than regular units when fighting in this fashion.

Let’s consider an example of a combat with supports. Returning to our Romans and Britons let’s give the Romans another unit of legionaries to their rear. In the case of the Britons we’ll give the horrible hairies two more warbands, one supporting to each flank. The Romans will have one unit fighting and one supporting, the Britons will have one unit fighting and two supporting. We’ll start off with the Britons charging once more so we can compare how they get on with the benefit of supports.

The fighting unit goes first with 9 attacks from the clash and the re-rolls as in the earlier example. If we assume the same dice rolls for this second example as for the first, the Britons score 8 hits and the Romans make half their Morale saves resulting in 4 casualties on the legionaries. Now, before the Romans fight, the supporting warbands add their attacks to the fight. Each warband has a short stat of 2 and therefore contributes 2 attacks – making 4 attacks in all. As both supports are identical and the dice rolls required to score hits will be the same we roll all 4 dice together. The supporting units need to score 4 or better to hit the enemy as supports never benefit from the bonus for charging, so an average roll will give 2 more hits and average Morale saves will result in 1 more casualty. The fighting Roman unit has therefore suffered 5 casualties in total.

The Romans fight back with 7 attacks from the fighting unit plus a further 3 attacks from the support. Both units require 4 or better to score hits. Hit inflicted from the supports don’t benefit from the –1 Morale save modifier for the pilum special rule, so it is necessary to roll the dice for the supporting unit’s attacks separately. Alternatively, and more conveniently, roll all the attacks at once but roll different coloured dice for the supports so you can tell which is which. Let’s imagine our fighting unit scores 4 hits of which the Britons save 1 on a reduced Morale value of 6. 3 casualties inflicted. With average dice rolls the supporting unit will score 1 or 2 hits – lets give them 2. The Britons take their Morale saves for these hits against their full Morale value of 5+ and we’ll assume they save 1 resulting in 1 more casualty. The Britons have suffered 4 casualties in total.

The Romans have taken 5 casualties against the Britons’ 4 so they are beaten by 1 and must take a break test with a –1 modifier to the 2D6 roll. If they score an average 7 this is reduced to 6 thanks to the difference in casualties and the Romans have a result of ‘give ground n good order together with supports’. This is the same result as for the one-on-one combat, but now we must take account of the supporting unit too.

Both the Roman fighting unit and the supporting unit are moved back 6”. This is how supporting units generally behave – they do what the unit they are supporting does. The Britons can now make a move, and they can use this move to pursue, retreat or stand where they are. In our case they will press forward back into contact. Supporting units continue to support where they can. The Celt supporting units therefore press forward on either flank so that they continue to offer support in the following turn.

In the following turn the combatants fight a further round of combat. The fighting units fight each other using their sustained stat, and the supports continue to offer their support using their short stat as before. Starting with the Britons as the winners of the first round, the fighting unit has 6 attacks and hits on 3s scoring an average of 4 hits. The supports contribute a further 4 attacks hitting on 4s scoring an average of 2 hits – remember supporting units never benefit from the bonus for charging or winning the previous round. The Britons therefore score – on average – 6 hits in the second round. If the Romans also roll average they will save half these hits and suffer 3 casualties bringing the total number of casualties on the unit to 8. As 8 is 2 over the unit’s stamina value of 6 the Roman legionaries are shaken.

Fighting back, the Romans have their 7 attacks and the supporting unit contributes another 3. Because the pilum rule has no effect in the second round of combat it is convenient to roll all these dice together: so 10 dice needing 4s gives 5 hits on the Britons. The Britons are now using their full Morale value of 5+ and so, rolling one dice per hit, will average 1 or 2 saves. Let’s give then 2 saves. The Britons therefore take 3 casualties (the same as their enemy) and their total number of casualties rises to 7. As the Britons’ stamina value is also 6 they are also shaken.

The result of this combat is a draw because both sides have suffered 3 casualties. However, because both sides are shaken both must take a break test. Units that lose a round of combat always have to take a break test, but shaken units also test if the result is a draw. This can potentially result in both sides recoiling or even breaking on occasions.

Before taking any break tests both sides have to re-allocate any casualties suffered in excess of their stamina value. Where units are not supported these excess casualties are discarded – as units never carry forward more casualties than their stamina value. But where units have supports any excess casualties are redistributed as equally as possible between them. The Romans have 2 excess casualties, so these spill over onto the supporting unit. The Celts have 1 excess casualty, which is allotted to one of the supports.

Having taken care of excess casualties both sides have to take a break test. As the result was a draw there are no modifiers, so it is just a straight 2D6 roll on the chart. Because the units are shaken any result of 4 or less will break them, 5 will result in them giving ground disordered, 6 or 7 will mean they give ground in good order, whilst 8 or more will see them stand their ground. For the sake of our example we’ll assume the Romans roll a 5 – meaning they give ground and become disordered. Both the fighting unit and its support move back 6” and once they have done so the fighting unit becomes disordered. This will stop it moving in its next turn.

To illustrate what happens when units break we’ll assume the Britons have rolled 4 or less and broken. The fighting unit breaks and is removed. When a fighting unit breaks any supporting units have to take their own test, taking into account any modifier if they lost the combat. So, testing for the first of the supports we roll a slightly above average 8 and the unit holds its ground. Testing for the second supporting unit we roll slightly below average with a 7, which means they give ground in good order. The unit is moved back 6”.

In this example the opposing units have fought to a point of exhaustion and both sides have effectively pulled apart with the central warband breaking. The Romans at the front of the formation are shaken and disordered, which will prevent them rallying in their following turn. As it’s the Britons’ turn next (as they charged in the first round) the surviving warbands may well decide to pile in again, taking advantage of their high clash value and the disordered state of their enemy. Also, because the surviving warbands only supported in the previous engagement they still have their wild fighter re-rolls. The Romans will be very lucky to survive this one!

Hopefully that’s given you a fair idea of how things work when it comes to hand-to-hand fighting. As you can see the rules are not especially complex. There are various extra modifiers to the various rolls to take account of high ground, fighting to the flank, fighting in open order, for shaken or disordered units, and so on – but these are not too numerous and are easily remembered. Similarly, there are modifiers that apply on account of different weapons, the Roman pilum being one example; others include the pike, lance, kontos, and long spear. As with Black Powder, the rules are intended to be adaptable, being easily modified to take into account localised historic differences in armament or capability. The trick with fighting hand-to-hand combat in Hail Caesar is to support fighting units with appropriate troops, and to keep your flanks from being enveloped as this imposes a penalty on a unit’s attacks and allows several enemy units to fight against you at once. Knowing when it is best to commit your commanders to combat is helpful too – as these fellows add 2 or 3 extra attacks to the fighting unit by way of inspiration – a not inconsiderable contribution in a close fight.

- FADRIL